Historically, communities that rely on forests, pastures or estuarines have been restricted and impacted by exclusionary conservation policies and practices. Foraging, farming and grazing communities have lost access to natural resources due to colonial forest laws. Additionally, post-Independence development priorities and their ecological impacts have resulted in exclusive and landscape-restricting solutions, like Protected Areas, which privilege large mammals and penalise traditional livelihoods.

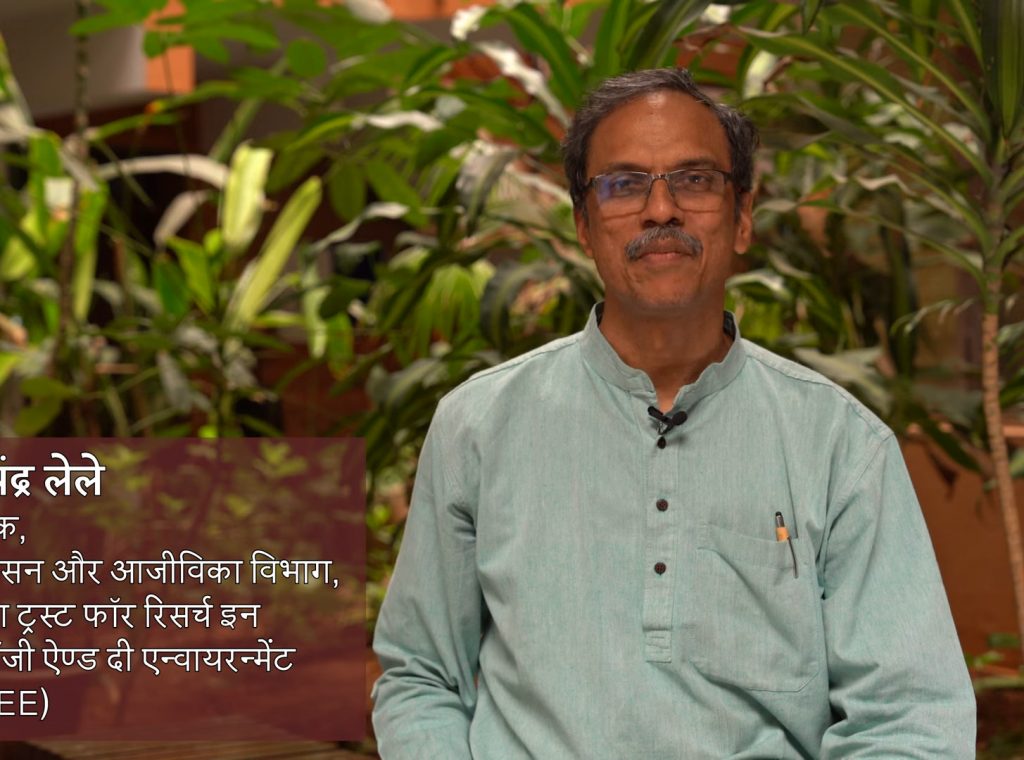

India has an established history of communities using and managing ecosystems. For 25 years, ATREE’s has focused on recognising the use of resources like non-timber forest products (NTFP) and traditional grazing practices as customary and sustainable. This programme seeks to research, understand and enhance strategies that enable forest and pastoralist communities to access natural resources and build resilience against exclusionary changes in policy and practices.

We collaborate with Adivasi communities in the Western Ghats to increase forest incomes and secure rights under the Forest Rights Act, 2006. We address the mislabeling of grasslands as wastelands in Maharashtra and protecting pastoral communities from detrimental land-use changes. We engage in action research along the western coastal estuaries by forming fisher organisations to monitor wetland biodiversity. Recognising that community well-being encompasses more than just income and assets, we have initiated human development assessments for forest and agro-pastoral communities in the Eastern Himalayas.

Livelihoods and cultural values play a vital role in sustaining and nurturing biodiversity in our forests. Forest dwellers, mainly Adivasis, engage in subsistence farming, cultivating millets, cereals and even cash crops, in addition to collecting NTFP. These products include fruits, berries, medicinal plants and honey. Over two decades, we have worked in the forests of the Western Ghats and central India, and accumulated valuable interdisciplinary insights into the ecological, social and institutional underpinnings of harvesting NTFP sustainably and enhancing livelihoods linked to these resource.

Semi-arid savannas and temperate grasslands have attracted far less scientific and policy attention than forests. In fact, grasslands, perceived as ‘wastelands’ have been misused for afforestation or conversion for construction. Our research and advocacy have focused on preserving the grasslands of the Western Ghats and central and western India as open, biodiverse ecosystems that support pastoralists grazing a variety of livestock. For nearly two decades, we have pursued research aimed at combining conservation efforts with livelihood needs that benefit communities like the Dhangars in Maharashtra’s savannas and the Todas in the Nilgiri Highlands of Tamil Nadu.

The aquatic and avian diversity of these habitats has gained attention and protection under the Ramsar Convention. Many such coastal wetlands, whether Ramsar-designated or not, are tourism hotspots. Kerala’s Vembanad estuary is one such. However, agricultural development and tourism have impacted water quality, biodiversity and local livelihoods. The Vembanad Community Centre has, since 2007, practised the ‘wise use’ of this wetland. It has enhanced the capacity and institutional networks of the local communities for its sustainable management